[Tinig] AI at Work: ChatGPT and Reflections on Automation

12 Apr 2023 | Smile M Indias

Even before we became aware of ChatGPT, the presence of AI or Artificial Intelligence in our daily life was already inevitable. For example, virtual assistants like Siri and Alexa use AI to understand and respond to voice commands, making it easy for people to perform various tasks without having to physically interact with their devices. AI powers our personalized newsfeed or playlists, and even the way digital interfaces like online forms and emails are able to auto-complete what we are thinking to write through AI. What, then, makes ChatGPT more exciting (or terrifying) for us today?

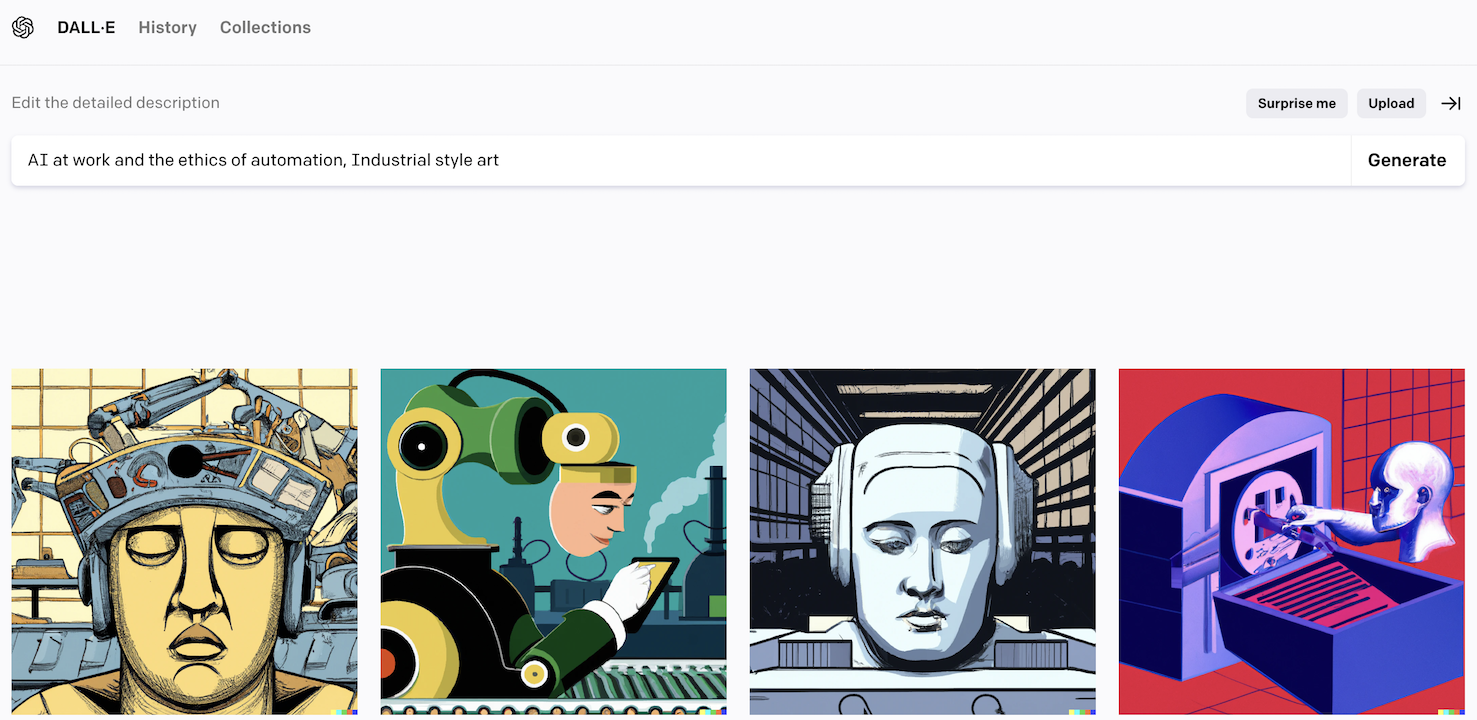

Prompt-based AI tools used to generate text and images are now becoming more common, at least, to us in Manila. Popular AI tools like ChatGPT, Dall-E2, and Midjourney use natural language to generate responses to a wide range of questions and prompts. Both ChatGPT and Dall-E2 were developed by OpenAI, an organization dedicated to advancing artificial intelligence safely and beneficially through the research and development of AI tools and platforms. Aside from the speed by which feedback is given to a prompt, what sets ChatGPT and these other tools apart from previously developed AI-supported tools or devices is its ability to mimic human response.

As we can imagine, there are limitless upsides to integrating these tools into our daily processes. Not only are we automating the production of our text and images, but we are also “calling upon” the collective intelligence of the internet to do so. Tools like ChatGPT have opened up the arena for other platforms to be easily adapted by the digital natives. Just last March 16, 2023, Microsoft released Microsoft 365 Copilot. Copilot is an AI-powered assistant developed to enhance the way we use the usual Microsoft products such as Word, Excel, PowerPoint, Outlook, and Teams. Just through simple prompts, this AI can analyze data, create visualizations, and transform documents into more audience-oriented communicative paraphernalia. It’s great, right? This allows us to make smarter use of our time for other more important tasks to be completed.

These platforms are able to do what they do because they get trained on very large datasets. Most training data is sourced from publicly available content and was preprocessed and cleaned to remove any personally identifiable information or other sensitive data before being used to train the model. This, then, opens up criticisms on the integrity of the training data of these AI platforms. There have been recorded instances that show that the responses generated by ChatGPT are categorically wrong. A case has also been filed against text-to-image AI generators for issues on copyright, consent, and compensation. Worse, there have been use cases that prove that AI tools, as products of the collective psyche of the internet, are not immune to racism and sexism. All these really boil down to the ethical sourcing of the training data used to power these AI tools.

Aside from issues of copyright and consent, we also now have to deal with questions of authorship and integrity of the body of work generated through AI. Books written through ChatGPT with illustrations created through Midjourney are now published for sale. Do we consider these literary works or should there be a distinction between literature produced by actual humans? If tech companies are now offering to pay US$300,000 a year to hire a prompt writer, how much premium should we then put on the prompts vis-a-vis the value of actually producing the text or image itself?

We’ve not yet even touched on the core issue of these tools at least in the context of the Philippines. Adaption of these AI tools may mean worsening the digital divide we currently are suffering from. Based on the latest data available from the International Telecommunications Union (ITU), only 6% of Filipinos aged 15 and above can perform basic internet skills and less than 1% can perform advanced digital activities. This is alarming because if we are looking to adapt these tools to make work and productivity more efficient, then we are definitely leaving behind the majority of the Filipino population if access to ICT is not yet first addressed.

The conversations around these tools, especially in an academic setting, mostly revolve around authorship and plagiarism. We ask how to ensure that the papers submitted are produced by students and not by an AI. On one hand, we have researchers at Stanford develop DetectGPT to help faculty assess the works of students and ensure these were not written by any large language models (LLM). On the other, universities like Cambridge have developed policies on AI Ethics that define how ChatGPT and other LLMs can be integrated into the academic process. We are being called to remain flexible in our encounters with these AI tools. For us in design education, this means we have to be more intentional about curating pedagogical experiences that highlight the process and not simply the product.

Amidst all these concerns, maybe the real question to ask is this: Why is there a need to game the system to begin with? Do we use AI for our tasks to make things efficient, so we can have more space for life? Or are we integrating these AI processes so we can be more productive and take on more work? What kind of culture are we really moving towards? So aside from creating policies around the use of ChatGPT and similar tools, maybe we are really being called to reflect on our relationship with productivity and how we can unlearn our continuous obsession with it. How can we meaningfully leverage these robots to do the work so us humans actually get to live?

Tinig is a monthly opinion and analysis series from the School of Humanities. The views expressed in this piece are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the School of Humanities or Ateneo de Manila University.