Umaalab: A reflection on TALAB 2004

22 Nov 2024 | Kristy Niña Ibarra, 5 AB Interdisciplinary Studies

In recent years, I have had a growing interest towards an often unseen sector in Philippine society: the indigenous peoples. Through my lessons, I have had the privilege to unlearn traditional, infrastructure-centered, and class-driven notions of the word ‘development’. The dominant kind of development that our administrations have been advocating for (and sadly implementing) are those that favor the privileged in society, not only destroying our environment in the process but also leaving behind those whose lives are most vulnerable.

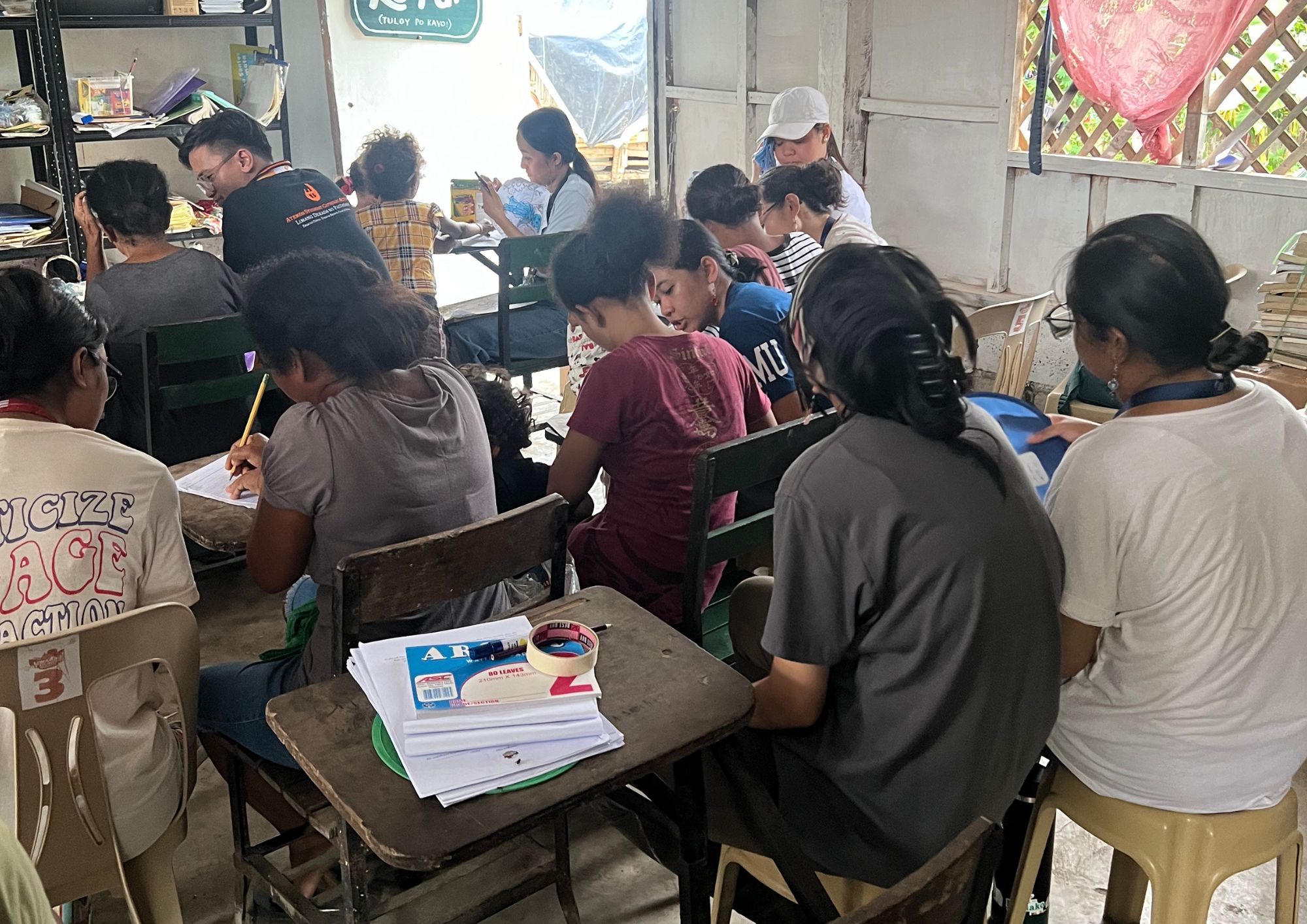

Last 20 October, through the collaborative efforts and management of Ateneo Student Catholic Action, Liwanag at Dunong, a non-government organization catered to advocating for and empowering indigenous Aetas, the Office of Campus Ministry and the Office of the Assistant Vice President for Ignatian Spirituality Formation, I was granted the opportunity to immerse myself in the world of native Aetas in Sitio Kalangitan, Tarlac.

It is one thing to learn and know about social realities, and a totally different thing to

experience them firsthand. Classes in development, communication, and anthropology in my years of college education have exposed me to the realities of indigenous groups: statistics about them are often few and far between, there is not much coverage and proper representation of IPs in media, they are often left behind by government programs, which by the way includes their access to health care and education, and as Kuya Stum mentioned, one of the volunteers and leaders at Liwanag at Dunong, “ang kasabihan dito sa Pilipinas, ‘malalaman mo na kapag malapit ka na sa mga katutubong lugar kapag wala nang kalsada.’”

Despite knowing all these, however, and despite the orientation briefing before the TALAB, nothing prepared me for the wave of emotions and discomfort that awashed me on the day of the immersion.

I was hearing narratives of Aeta kids bullied in the classrooms because of their skin color and thick, curly hair; of elders and adults, when selling their goods, overhearing, “diyan tayo sa Aeta bumili kasi mga mangmang sila, madaling lokohin.”

As I was listening to the volunteer leaders sharing stories that the Aetas have told them, and hearing, “Walang tumatabi sa amin kapag sumasakay sa bus o jeep, iniiwasan kami ng mga tao.” “Nahihirapan kami kapag umuulan dahil ang putik ng daan. Pero hindi kami pinakikinggan ng lokal na gobyerno rito,”

I felt a sense of desolation. I felt helpless, too. I felt moved, and yet, I also felt like, try as we might, there is still so much work to be done, and there is much neglect not only from local authorities but also from ordinary citizens who enable oppression and discrimination.

Now, days after TALAB, my thoughts have been frequently going back to the people I

met, the faces I saw, the names I knew, and the stories I heard. And, I’ve been frequently asking myself, where is God in the inequality that I witnessed?

Nasaan ang Diyos?

As I look back, reflect, and continue to simmer in the movements of desolation that I felt in the community, and as I try to battle the temptation of questioning God’s existence in the midst of injustice and oppression, I have come to realize that God—our ever-present,

ever-loving, all-compassionate God—is a God who suffers. A God who suffers with us.

God is close to the brokenhearted, ika nga.

As I bring my experiences, feelings, and thoughts about the immersion to prayer, I have come to find the subtle presence of goodness and courage that I encountered in the community.

God is present in the perseverance and the openness of the Aeta elders in welcoming us outsiders, and allowing us the gift of a glimpse into their world, their culture, and their language. Despite the discrimination and oppression they have experienced both from authorities and structures that are meant to protect them, as well as the indignance of outside non-indigenous, they still choose to open their doors to volunteers who are, in essence dayuhan or strangers, to the Aeta culture.

God is present in their kindness and peaceful nature—in their collective culture and

emphasis on unity and community.

God is present in their elders—who strive so hard to fight for the next generation, passing down to the younger ones their wisdom and cultural heritage.

God is present in the very lives of the Aetas—accompanying them through their beliefs

and traditions, different may they be from ours.

And, most of all, God is present through the voices of those who fight for them—in Ate

Ning, Kuya Stum, and all the volunteers who sacrifice their time and health, going outside of

their comfort zones to uplift and empower our Aeta brothers and sisters.

I once read from a quote on Facebook, many years back, “that doing nothing in the face of oppression and injustice is just as bad as siding with the oppressor.”

Our call to care for our common home is a call to uplift, protect, and empower people,

especially those whose lives are intricately intertwined with the environment.

Sa lahat ng naranasan ko, tumatak sa akin ang realidad na hinaharap ng ating mga

katutubong kapatid. Tumalab sa akin ang TALAB, at ngayo’y umaalab sa aking loob ang

panawagang ipaglaban ang ating mga katutubong Pilipino.

And so, I leave you with these questions:

What are the ways in which I care for and stand with the call to care for our Common Home?

How may I concretely show support and help to bridge the gap in uplifting the lives of and empowering my indigenous brothers and sisters?

And, lastly, in what ways can I show love—concrete, action-driven love—to quell instances of indigenous discrimination within and outside of my immediate community?